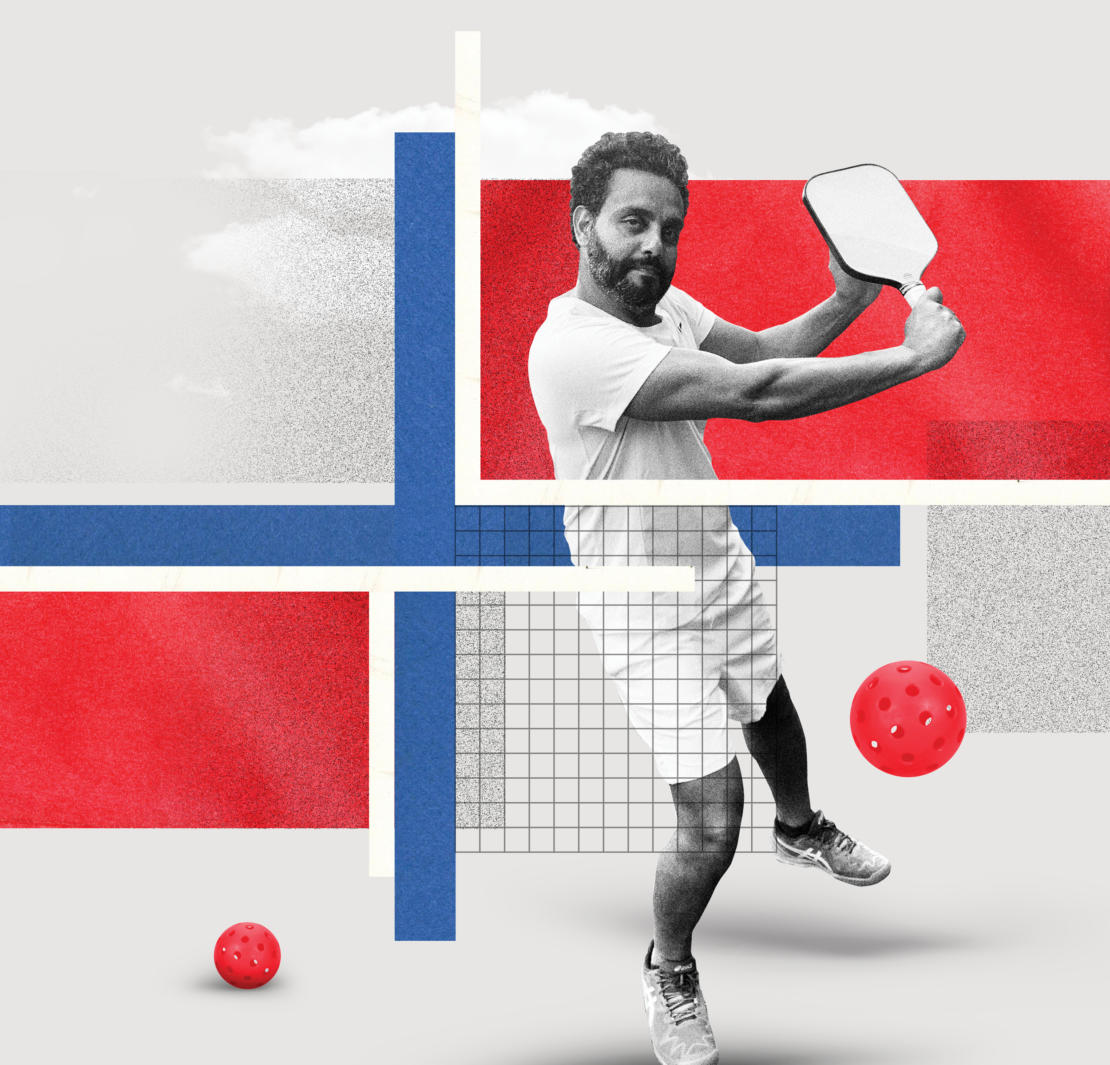

WHEN LONGTIME Oslo resident and American expat Peter Girgis visited his brother in California several years ago, he had no idea that playing a few pickleball games in a park in Pasadena would alter the course of his life—and help spur pickleball’s popularity in Europe. “My brother planted this idea in me,” the 43-year-old says: Why don’t you bring this sport to Norway?

Girgis was intrigued by the concept but didn’t know where to start. Fortunately, his neighbor James Macpherson became equally excited about the idea, and together they mapped out what they hoped would be “the future of pickleball in Oslo.” Girgis already owned a box of used pickleball paddles and balls, and he applied his background in design to create a simple website: pickleballnorge.com. Most important, Girgis had a gut feeling that pickleball’s popularity in the U.S. meant it would eventually boom in Europe too. “We just had the sense that it was going to happen,” recalls Girgis.

Norwegians began visiting the Pickleball Norge website out of curiosity, and the International Federation of Pickleball took notice too, allowing Pickleball Norge to act as Norway’s chief pickleball body. Girgis also visited Oslo Tennisklubb, one of the city’s largest tennis clubs, where he persuaded them to host pickleball games every Friday.

NORWAY’S SPIN ON PICKLEBALL

Pickleball games in Norway are typically played using a linguistic mash-up of English and Norwegian. The score, for example, is often verbalized in Norwegian (e.g., en-to-to, meaning “one-two-two”). Banen means “court,” and linje refers to a court line. But the non-volley zone isn’t called kjøkken, which means “kitchen.” Girgis says, “You call it ‘the kitchen.’” Similarly, a dink is just a “dink.”

One of the most significant milestones for pickleball’s growth in Norway came when Girgis taught pickleball to employees at a multiuse sports venue called Tøyen Sportsklubb—and the venue promptly started offering pickleball on its indoor courts three days a week. The club is in an ethnically diverse area of Oslo, and many of the pickleball players are kids with varied, international backgrounds. This carries personal meaning for Girgis. “When you go there, you don’t see the blonde-haired, blue-eyed demographic of Norway,” he says. “My family comes from Egypt—I’m the first-generation American—and I immigrated to Norway, and here I was possibly bringing a conduit of achievement, of hope, of interest, of possibility, to a young group of people who sometimes have very little opportunity.”

Girgis says Pickleball Norge currently has 50 members and approximately 400 Instagram followers (@pickleball_norge). He admits those figures don’t sound “exceptional,” but he points out that numbers don’t always reflect pickleball’s ability to change a person’s life. “The activity that happens in those few hours in the indoor sports hall—it carries so much weight on an individual level,” he says. “It starts small—everything starts small.” The proof that Girgis launched something special is that games are popping up at venues and on outdoor courts all around Oslo. As he says, “The seed has been planted.”

The borrowing of English words is not surprising, given that Oslo is a fairly international city, with pickleball players hailing from Somalia, Sweden, Denmark, Greece, Lebanon, France, the United States, and elsewhere. This diversity is a highlight of round robin sessions, the most common form of organized play in Norway, which make it easy to meet people and make new friends. “Sport is a great unifier of people,” Girgis says. “You can simply hit this ball over the net, back and forth, and that sense of achievement has united you and me; now we can play together.”

NORWAY’S SPIN ON PICKLEBALL

Pickleball games in Norway are typically played using a linguistic mash-up of English and Norwegian. The score, for example, is often verbalized in Norwegian (e.g., en-to-to, meaning “one-two-two”). Banen means “court,” and linje refers to a court line. But the non-volley zone isn’t called kjøkken, which means “kitchen.” Girgis says, “You call it ‘the kitchen.’” Similarly, a dink is just a “dink.”

The borrowing of English words is not surprising, given that Oslo is a fairly international city, with pickleball players hailing from Somalia, Sweden, Denmark, Greece, Lebanon, France, the United States, and elsewhere. This diversity is a highlight of round robin sessions, the most common form of organized play in Norway, which make it easy to meet people and make new friends. “Sport is a great unifier of people,” Girgis says. “You can simply hit this ball over the net, back and forth, and that sense of achievement has united you and me; now we can play together.”